I had a teacher who said atheists almost never cope well with bad people actually getting away with it. He said the human soul years for some kind of justice. The idea of Adolf Hitler wining and dining over stolen art while tens of thousands of kids are shoveled into his ovens or blown apart with his shrapnel and never getting his just desserts is a pill nobody wants to swallow. I thought about this a lot while watching the story of Kilmar Abrego Garcia. It goes against every single principle a nation devoted to freedom and the rights of the individual could possible have. If sending a man to a foreign torture dungeon without trial isn’t wrong, then, like Abraham Lincoln said about slavery, nothing is wrong. As of April the 17th, Senator Chris Van Hollen of Maryland was able to meet with Garcia, confirming that he is alive and in reasonably good health. This is very good news, because it suggests the liberal tears are working. The tiny Central American nation of El Salvador evidently has a lot invested in keeping something too nasty from happening to the poor guy, because lib ownery may not be advantageous in three years and nine months from now if you’re smaller than New Jersey and in our hemisphere. Nice country you’ve got there, Mr. Bukkake. Would be a shame if Mayor-President Pete had it turned back into America’s fruit plantation.

The reason why the incident is so vile is Garcia, a completely normal guy, was deported to a torture camp by mistake. The powers that be in the U.S. and El Salvador have refused to return him. Why? Apparently so Trump, the softest coward in the world, can larp about how tough he is on the internet. Under the Supreme Court case Trump v. U.S., Trump himself is never going to face any kind of punishment. He will die fat and rich and happy, after fleecing cash from his flock to the tune of billions, after extracting huge sums of taxpayer money to keep him breathing and comfortable well past his natural lifespan, and after conning eight years out of a country full of people vastly superior to him. Garcia, meanwhile, a legal immigrant and dad with multiple American citizen kids, is going to spend his next four years as a captive in a banana republic. All because feds mistook his Chicago Bulls cap for gang memorabilia, and because Trump, who again, is going to get away with all of it, wanted cool TV. As an atheist, woof.

But of course, right there, I just fell for it. Emphasizing Garcia being a legal immigrant and upstanding American resident drives home the injustice of it all. To defend themselves, Trump and his faithful have taken to the airwaves, the big screen, and the internet and falsely accused Garcia of being none of these things. I have to keep reminding myself that Trump could molest their kids and they’d still be doing gleefully waging the culture war on his behalf. Of course, the implication behind the battle (“Haha, look at you libs, defending a guy who murdered 30 [white, Christian, heterosexual] babies!” “Look at you MAGA monsters, sending legal immigrants to prison camps for no reason!”) is the situation becomes less unjust if you just make Garcia an illegal immigrant without kids who might actually be a gang member. Which is true. Even I can’t actually tell you what happened to this guy is exactly morally as bad as what happened to the hundreds of actual gang associates who met the same fate. But ideally, the discourse would point towards a truth, a self-evident truth, some might say: these things happen when you torture people without a trial. Either out of malice or incompetence, the government cocks up— something it’s done in more than one case one already, in only three months amongst a couple hundred deportations of immigrant gang suspects— so there needs to be a system in place that gives the defendant, the underdog in any confrontation with the all-powerful federal government, a fair chance. Even then, people will be convicted unjustly, because there’s bad actors and mess-ups at every single level of humanity, so the state can’t have the right to awfully and cruelly punish people, even if they’re guilty. Garcia isn’t the only innocent man who is down there, and the scariest part is we’ll never know about a lot of it because Trump and his minions are so contemptuous of a process they aren’t smart enough to understand.

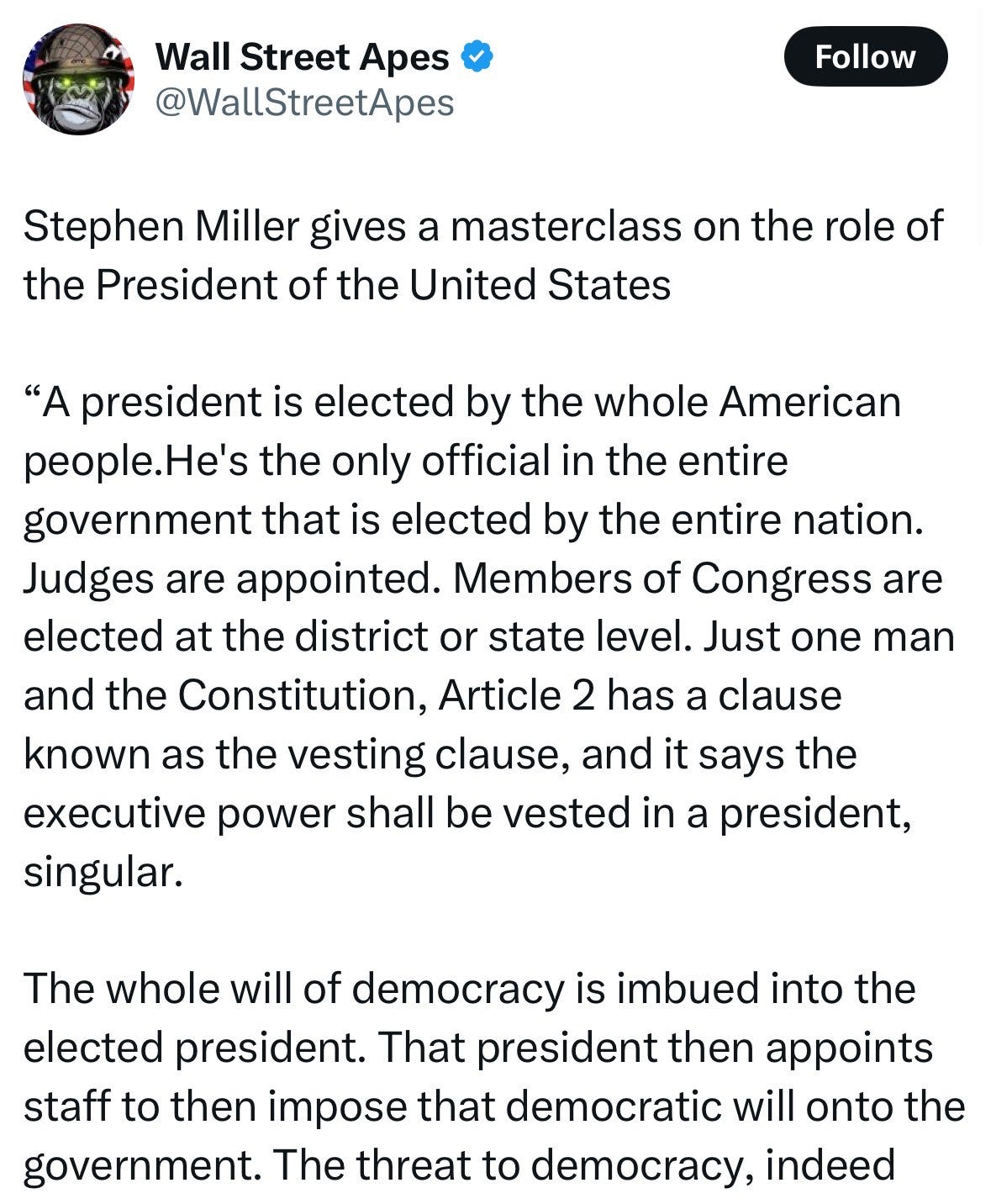

(Yes, the image above is from the White House’s Twitter.)

The things in the last paragraph are very Founding Father-y, English Roundhead-y sentiments. The right to a fair trial and the right to not be extravagantly tortured are both in the U.S. Bill of Rights. All Americans have these rights, and while not everyone on earth is entitled to them, the Fifth and Eighth Amendments that should be protecting Kilmar Abrego Garcia were introduced then and upheld now as common-sense elaborations to Thomas Jefferson’s declaration that all men are created equal with these certain inalienable rights, so it follows no men should be in El Salvador’s torture camp. It is not about whether the person the state is after is morally good or not. The modern American right has consistently, even while nothing else about them has been consistent, failed to grasp this. They were the ones who believed in banning the flag to jail hippies, were the ones who conjured up mushroom clouds to justify Bush putting people in black sites without trial, and now are the ones shamelessly defending Trump doing the exact same things but even more egregious. But at this point I’m probably preaching at the choir. The only point I’d like to throw out there before moving on: the same ugly instinct on the right that supported George W. Bush pummeling Iraq is the same ugly instinct pumping a fist in the air when Trump gleefully tweets about brutalizing MS-13 members. Both are examples of mob politics, where strong, manly leaders tell a story about an enemy that’s simple, and then rain down the awesome fury of the state apparatus as a deliberate ploy for political control. Both represent what a certain HHS Secretary’s dead father called the “darker impulses of the human spirit”, and are familiar tools in the arsenal of every dictator, from Korea to Russia to El Salvador.

This is where it gets complicated, because the law Trump (dubiously) invoked to initiate the deportations, the Alien Enemies Act of 1798, was approved by a huge portion of the Founding Fathers serving in government then, along with the far more controversial and no longer active Sedition Act, which made it a criminal offense to print something “malicious” about the government. George Washington approved, and felt the Jeffersonian Republican Party the Acts targeted was a subversive, dangerous element more loyal to Revolutionary France’s ideals than America’s. Alien and Sedition. Adams eventually came to regret signing the laws, and his successor Thomas Jefferson repealed all but the Alien Enemies Act. At this point, the First Amendment, every word of which was compromise language to begin with, had never been tried in court (it wasn’t entirely clear what that process looked like) and the country was facing an unprecedented national emergency where it was neither ready to go to war but also needed to respond with force on an international scene it was new to. The Acts were met with widespread resistance from the Jeffersonian Republican Party, with Jefferson himself secretly threatening Kentucky’s secession. Censorship threats and civil war threats are as old as America itself. Both Jefferson’s Kentucky Resolution and Adams’s Sedition Act are chapters in American history we’re not proud of, and familiar hallmarks of the ugliest parts of politics today. The difference, of course, was at the root John Adams very much did believe in some universal concept of fairness that wasn’t dependent on what benefited his politics in the moment. Adams successfully negotiated an end to the Quasi-War with France Alien and Sedition, offending his most powerful supporters and dividing the Party right ahead of an election year. When Adams lost to Jefferson, he conceded, beginning the peaceful transfer of power that every President until Trump honored. And Jefferson too believed deeply in the institution, and when in power he would go to extensive lengths to preserve and grow the Union. The grave misjudgments these two made should be evidence that even the most gifted people with the best of intentions go wrong, and government has to painstakingly balance all interests against each other to prevent any single one from getting too much power, so random kids with water pistols aren’t subjected to violations of international law.

The right isn’t like this today. The reason is punditry. Interestingly, the Sedition Act was basically directed at 1798’s punditry problem. There were a bunch of Jefferson-allied pamphleteers who were bitterly partisan, constantly raised frivolous accusations against Washington and Adams, and generally used inflammatory rhetoric and opinions to generate engagement, using conspiracy theories to convince their audience they were the only ones they could trust. Federalists thought they were trouble for national unity, and might bring the violence of the French Revolution to America. Which raises another curiosity— why were the guys who started the trend of republican revolutions in the western world so down on the French Revolution? This became especially true by 1793, when French King Louis XVI famously lost his head. In fact, one of the initial defining characteristics of the early Party divide in the United States was the very anti-France Federalists, versus Jefferson’s more France-curious faction. While it’s impossible to distance the long and convoluted tale of Franco-American relations from base power politics, there also was an ideological difference between the two projects. Take a look at this specimen I found on right-wing Twitter:

You can guess where he’s going. Like G. Elliot Morris (formerly the FiveThirtyEight guy) says, this is absurd in a way that beggars the mind, even by the standards of right-wing punditry. What strikes me here is just how many French Revolutionary concepts and adjectives Stephen Miller broke out; the “General will” is a central principle in the thought of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, an utterly brilliant polymath widely regarded as the Revolution’s philosophical godfather. Rousseau is a curious figure to me, because he’s mostly been left behind by the intellectual world. The strenuous attacks on his work and ideas from conservatives and classical liberals eventually won out, the French Revolution ended with Napoleon Bonaparte declaring himself Emperor, and in the radical tradition Rousseau was overshadowed by thinkers in the vein of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Today, my copy of The Social Contract, a Penguin Books paperback, warns the reader that some have seen Rousseau’s ideas as an early egalitarian manifesto, and others have seen it as a blueprint for tyranny. And there is something that feels distinctly discredited about Rousseau. Many historiographers use the French Revolution as a handy cut-off point between modernity and not-modernity, the same way Edward Gibbon used the 476 deposition of Romulus Augustulus as the boundary between classical antiquity and the Middle Ages. And the reason for that is plain enough— Rousseau really is on the cusp of modernity, and the French Revolution his writings kickstart is the thing that every single modern political philosopher, from Marx to Edmund Burke, is reacting to.

Rousseau, on his face, might not strike you as a likely candidate for the right’s new Guy. The Social Contract opens with “Man is born free, and yet everywhere he is in chains.” Rousseau was highly critical of wealth inequality, a supporter of participatory, majoritarian democracy, and was a pretty impious agnostic who believed being a deadbeat dad to the many kids he sired with prostitutes was fine because he hadn’t entered into any kind of social contract with his kids. Rousseau drifted between the Calvinism of his native Geneva and the Catholicism of France, seeing both in terms of legal systems with different merits. He ran in the same crowd as guys like Voltaire and Diderot, who are practically the originators of modern secular criticism of the Catholic Church. Nietzsche considered him “the tempter” of the lower classes. Nearly every single serious conservative since the year 1793 not only has violently negative things to say about the French Revolution Rousseau inspired, but one could argue the entire intellectual exercise of conservatism itself is a reaction to the French Revolution.

Even so, I think there’s a straighter line between Rousseau and Stephen Miller than one might think, and I think this is something worth looking at because the MAGA Revolution is just getting started. We’ve got three years, nine months of this left, may Reason save us, and there’s never been a better time to figure out what degradations of liberal philosophy got us into this mess.

The General Will

Stephen Miller’s little theory crash course, delivered characteristically insincere and seemingly completely contradicting the right’s pious assertions that we’re not a democracy and that’s based actually, is useful. It’s about the most un-conservative thing you could ever see spill from a public figure’s mouth. Conservatives from Burke to John Adams to the Bourbon monarchs go apoplectic when they hear these ideas, and when they’re put into practice all the armies of Europe scramble to put out the fire before it can spread. But of course, you can easily make a similar argument for the things coming out of the right-wing pundits’ mouths over the last eight years or so, and it wouldn’t be hard to cook up less convincing but still potent arguments about the Tea Party and neoconservatives and every grassroots right-wing political movement in America since the New Deal. I don’t want to lean too hard on my own ideas, which often change, but like I’ve said before I think a key part of the right’s political identity is how the New Deal, World Wars, and Civil Rights movement marginalized it from the real organs of power in American society, such as academia and bureaucracy. I think it’s reasonable to say Trump supporters are not conservative in the revolution-skeptical, institutionalist, hierarchical way John Adams and the Federalists were, because they have no functioning hierarchies and institutions. Trump supporters are the guys prancing around in small-town Walmarts wearing Thomas Jefferson t-shirts about shooting at the government! The Alien Enemies Act was supposed to help Adams get rid of their foreign buddies.

However, it would also be pretty dumb to suggest the Republican Party isn’t meaningfully right-wing, because it is. It resents change. It really does consciously want to return to the white-picket fence in the 1950’s with the white man married to the white woman with the two white kids and the golden retriever buying $20 of groceries every other week on the white man’s lonesome income. If you really wanted to be charitable, you could even say the right’s embrace of revolutionary tendencies is a somewhat sincere, if pundit aggravated, response to left wing abuses. In other words, the left took over the entire system and dismantled the Constitution, so now the right doesn’t care about the Constitution and just wants to win. I think the best way to describe the Republicans right now is reactionary and right-wing, even if they’re demonstrably less right-wing under Trump than they were under Romney, while simultaneously not being conservative.

And while describing Rousseau as right-wing feels like a meme, it wouldn’t be meaningless either. Take Discourse on Inequality, Rousseau’s second most famous work, where he explores his most misunderstood and well known idea, the “noble savage”. Rousseau consistently believed civilization and technological progress were corrupting influences on people. In his state of nature (remember, this predates archaeology and Darwinism, so the state of nature is best understood as a thought exercise, rather than a meaningful scientific declaration), humans are by definition good and happy because they don’t have the tools to be unhappy. The man in his natural state walks around, eats berries, tries not to die, mates with a woman in the forest and creates a nice little nuclear family. Since all he’s worried about is food and sex, he doesn’t kill nearly as much as those of us living in the age of nation-states and extractive capitalism do. What separates Rousseau from primitivists like Ted Kacynski— who he directly inspired— is Rousseau thought the cat was out of the bag on technology. Rousseau agreed technology had made mankind less free and less happy, and introduced private property and the state to human relations, but he also believed these things were inevitable or at any rate unstoppable once they got started. For Rousseau, political remedies, insomuch as he recommended them, was about how to make sure private property doesn’t become crippling wealth inequality, and how to make sure governments don’t become tyrannical.

That plays into how Rousseau understands legitimate power. A conservative like G. K. Chesterton sees tradition as democracy of the dead. Polities are a contract between us, our ancestors, and our descendants. Institutions often exist for good reasons. A liberal like Locke, or Thomas Jefferson, might sound a lot like Rousseau, but for them the validity of a state comes from the respect it pays to the self-evident, God-given rights every human is born with. For Rousseau, rights ultimately are contained in the human community. A key Rousseauvian concept is even if man in his state of nature does just have something wrong with his brain and decides to do terrible things to the other noble savages for no reason, Rousseau doesn’t see this man as immoral because immorality itself doesn’t exist yet, just like how Adam and Noah might’ve been rulers of the world at one point but this wasn’t meaningful. There hadn’t been a lawgiver— such as Moses, Lycurgus (the author of the Spartan Constitution), or John Calvin— to hash out the rules. In Rousseau’s mind, the state and private property came to exist at some point when human populations became dense enough and interconnected enough for someone to stake out a square of property and claim it, and once that happened, a process Rousseau admits he’s ignorant on the mechanics of, there was no turning back. Authority has entered the human world. The question that consumes Rousseau is what kind of authority is legitimate.

Remember when Trump quoted Napoleon on Twitter? “He who saves his country breaks no law?” Napoleon greatly admired Rousseau and was one of many talented educated young men the Revolution catapulted into the global spotlight. Rousseau didn’t think a social contract ceding the power of all your descendants to, say, an absolute national monarch (Thomas Hobbes’s original conception of a social contract) could be legitimate. Since men’s right to command themselves politically is inalienable, the only fair, legitimate source of political authority is a government where people are masters of themselves and accountable only to themselves, like democracy. This is the origin of the Rousseauvian “General will”— the casus foederis of all laws. For Rousseau, laws are only valid if they are born of the General will. Rousseau says he who doesn’t save his country makes no law to begin with, at least not one that’s anymore legitimate than a guy on a horse taking 10% of your crop from you because the Catholic Church said he could.

Rousseau goes on to say under the regime of the General will, the instruments of the state become instruments of liberty. He cites the practice of Venetians (a state he very much approves of) writing “LIBERTY” on the gallows and prisons, and says this is the way it ought to be. When the state is really and truly acting in accordance to the General will, when it is bringing the hammer down on lawbreakers it’s doing exactly what it should do, and protecting the polity of free men engaged in a legitimate social contract from problematic outsiders and internal troublemakers. Which is the crux of Stephen Miller’s argument: Trump has the mandate of heaven. He was elected specifically to get rid of the illegals, so he has quite a bit of legitimate moral authority to get rid of them. Does it really matter if an unelected wizard a President from twenty years ago and fifty members of a body where Vermont, Texas, and New York all get the same amount of votes connived to put on a federal court says to stop? No. Trump has the General will and the judge is just a nail-biting weakling.

You can find all sorts of holes when you try to apply Rousseau’s political beliefs to the American right’s political goals, not least of which is the absurdity of invoking the General will when Trump didn’t even win most people’s votes. Rousseau knew this, and that’s why he preferred the small, homogenous city-state republic to the big imperial nation. Rousseau’s favorite polities were Sparta, the early Roman Republic, Geneva, etc. where laws could actually be said to emanate from the people. The idea of a General will emerging from a country like America, where we have two parties representing roughly equal sections of the populace that consistently trade power every ten years or less, is patently ridiculous and I’m not suggesting The Social Contract says the Salvadorian torture dungeons should have “LIBERTY” plastered over that mound-looking red mass on Google Maps. But this is one of those areas where the reality of life in America overrides the right’s philosophical impulses and they can’t do anything more about it than Rousseau. Right wingers have a very Jeffersonian conception of what makes a happy citizen, one that’s impossible to put into practice now. They like the little rural yeoman with his humble farm and big black gun, and distrust sprawling, urban centralism trying to impress itself on Middle America. Rousseau would probably agree.

This is the basic story of right wing political migration before MAGA colonized Florida. It was libertarians trying to take over very rural, very white and reasonably well off New Hampshire, and ancestral residents of conservative Orange County scared off to Idaho by the Rodney King riots. It was about finding something smaller and more homogenous, which is where you can get the purest distillation of the General will, where stuff like the Civil Rights Act isn’t even a conversation. To prove my point, imagine if Trump’s “plan”, or maybe more appropriately the chud utopia his most devoted and conscientious supporters actually want, came to fruition. What would Republican Town really look like? Many cultural and political goals the right pursues are unrealistic, like simultaneously wanting a mighty American empire and also harboring a distaste for big government, or simultaneously embracing the culture-crushing tornado of market capitalism and the dying life of the small town. But laughing off the yearnings of the Republican soul would be pretty foolish. To the extent that they mean anything, they are Rousseauvian. Stranded in the modern world, they want a state that preserves order via homogeneity, fiercely looks out for its own interests, and derives its legitimacy from how loyal it is to real America, which wasn’t too far from how the French Revolutionaries saw themselves. True, unlike MAGA they didn’t hearken back to a rustic small-town past and instead towards an urbane future dominated by metal and science, but it it is also very hard to find any actual predecessor for MAGA politics in the American canon. Almost no thoughtful person, not even on their side, really sees the ghost of John Adams when Trump invokes the Alien Enemies Act, like how nobody with any intellectual integrity (this excludes most pundits) really sees anything meaningfully Christian in that AI video of a pleasure resort full of bikini-clad brown people on top of the holy land’s ruins. MAGA is completely jokerpilled— society has wronged them one too many times and now billions must die, until they’ve got their communally owned e-girls, streets free of Haitians, and schools without odd looking transgender people. Like the French Revolutionaries, there’s nothing sacred about the Bastille if it’s not meeting the demands of the General will, and since any concept of the General will depends on homogeneity, there are a lot of fake Americans who need the boot soon.

The differences between the French and American experiments probably don’t have to be stressed, but I will a little anyway. George Washington, right after winning a long and brutal war that left him with the largest army in the western hemisphere, surrendered his commission (see the painting at the beginning) to the young democracy he saved on the battlefield— an act King George III said made him the greatest man of his age. Napoleon Bonaparte foisted a crown on his own head and lead France into a decade-long slaughter to keep it, which ended with 20% of the French male population dead and the Bourbon monarchs back in charge. The American project’s survival was its distinct absence of a General will or anything like it. Its federalism, division of powers, and unique resistance to booting the bad guys are the hallmarks of its success and practically every positive development in the last 250 years has invoked it. Both Rousseau and the Second Continental Congress might’ve agreed in the innate liberties people were born with, but they had radically different assumptions about how humans worked and what polities were supposed to do. Rousseau was a creature of the French intellectual scene of his time, where scholars were seriously attempting to encyclopedize all human knowledge. The American colonies were settled by a lengthy array of religious dissidents who wanted to build whatever kind of church they wanted. The men of the French enlightenment really thought the age of reason was right around the corner, while the men of, say, the Plymouth Bay Colony followed a religion that believed there was a monster waiting in every man.

This is where Rousseau deserves credit. Unlike the other intellectual architects of the French Revolution, Rousseau saw the dangers in technology dragging man forward. Many of his contemporaries were more progressive, in the sense that they saw history as an endless upward slog to an enlightened society where everything ran off of pure reason. While, say, the Marquis de Condorcet rhetorically wondered whether “Is there on the face of the earth a nation whose inhabitants have been debarred by nature herself from the enjoyment of freedom and the exercise of reason?” in the first chapter of The Progress of the Human Mind (Condorcet lost his head to the more radical factions of the French Revolution), Rousseau saw humans as naked, cold and alone in modernity, and believed a republic was supposed to honor their collective liberties. I find him to have a certain intellectual humility a lot of his contemporaries don’t. It’s difficult to imagine, say, Thomas Paine informing his reader that plenty of past societies practiced slavery and other practices maintaining unjust, natural hierarchies as a matter of their own admirable survival and seeing the utility of both Mosaic Law and the Prophet Muhammad’s decrees, but Rousseau did all of that. He, however, was only one smart guy who had been dead for a decade by the time the Revolution he inspired happened. When it did, wily politicians rapidly knifed each other fighting over who actually represented the real General will, which is about the way the Donald Trump experiment has turned out, and by nature must turn out— a bunch of idiots breaking things for no reason, because the complex, imperial nation Rousseau regarded with caution doesn’t have an easily distilled General will, and attempts to create it in one will amount to the hand cutting off the nose to spite the face. Rousseau knew this. Unfortunately for us, the right-wingers nodding along to Stephen Miller’s Constitution lessons have that uniquely progressive, French Revolutionary flaw where they assume they’re in the right and the 70% of the country that doesn’t live their way or see it their way either doesn’t exist or needs to be treated like termites.